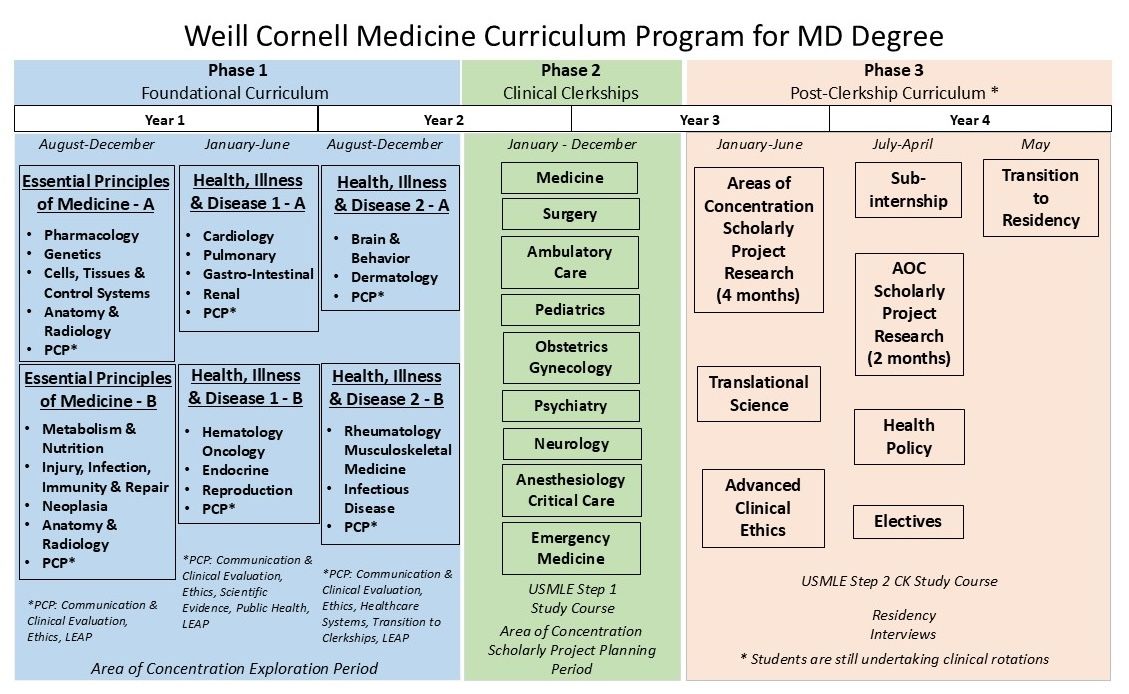

Curriculum Overview

A great doctor’s foundations are firmly rooted in their medical training and education, and this idea lies at the heart of Weill Cornell Medical College's exciting new curriculum.

In 2010, in response to emerging innovative medical technologies and rapidly advancing scientific discoveries, a committed group of faculty, students and leadership began to plan our current curriculum, which began with the incoming Class of 2018.

Phase 1 – Foundations

- Essential Principles of Medicine (EPOM) Parts A & B (includes LEAP)

- Health Illness & Disease 1 (HID-1) Parts A & B (includes LEAP)

- Health Illness & Disease 2 (HID-2) Parts A & B (includes LEAP)

Phase 2 – Clerkships

- Anesthesiology/Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Medicine

- Neurology

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Pediatrics

- Primary Care

- Psychiatry

- Surgery

Phase 3 – Scholarship and Advanced Clinical Skills

- Area of Concentration – Block 1 (16 weeks)

- Area of Concentration – Block 2 (8 weeks)

- Translational Science

- Advanced Clinical Ethics

- Health Policy

- Transition to Residency (Boot Camp)

- Electives (16 weeks to include 4 weeks outside of their chosen career/specialty area)

For MD-PhD degree information, please visit the MD-PhD program website.

Longitudinal Educational Experience Advancing Patient Partnerships (LEAP)

LEAP (Longitudinal Educational Experience Advancing Patient Partnerships) is an innovative program that allows students to participate in the healthcare experiences of assigned patients who reside in their community, from the beginning of their medical school experience and continuing throughout their four years of medical school.

The goals of the LEAP program are:

- to allow students to partner with patients early in their medical school careers

- to provide a clinical experience that will complement and enrich basic science learning

- to help students understand the complexity of the healthcare system, and appreciate patients experiences within the system

- to foster humanistic and culturally sensitive medical care

- to explore the meaning of professionalism and collegiality

- to experience the richness of the doctor-patient relationship over time

First-year students are generally assigned two patients initially (this number may increase over four years). Students are expected to engage with their patients at least once a month, ideally in the context of a medical office visit, hospitalization, home visit or phone call. Students meet monthly in small groups with two faculty members to discuss these experiences, review the clinical and psychosocial dimensions of patient care, and reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of the healthcare system.

As students transition to their third and fourth years, they maintain a role in the care of their patients, but also adopt a teaching and mentoring role for first- and second-year students entering the program.

Frequently Asked Questions

How are patients assigned?

Patients are assigned to each student before they begin the program. Every effort is made to select different types of patients to give the students a diversity of experience. Students will receive their patients' names and contact information during the first LEAP session.

Do students have a choice in the type of patient assigned to them?

Students can express an interest in a certain type of patient (i.e. pediatric), but there is no guarantee that their request will be filled. There are a limited number of patients, and we cannot promise that students will be assigned a patient that fits their primary interests.

How are students introduced to patients?

At the LEAP student orientation, students will be given the names and contact information of their patients. They will also be introduced to second-year students working with the patient. Students are expected to reach out to their patients and set up a time to meet.

Will patients expect students to provide medical advice?

Under no circumstances should a student provide any medical advice, other than to help a patient understand the instructions/advice given by their doctor.

What if I don't know the answer to one of my patient’s questions?

It is fine to say that you don't know the answer. The patient understands that you are a student and not expected to have all the answers.

Do we have to see patients in pairs or can we go alone if necessary?

Either way is fine. If one student cannot make an appointment, it is fine for the other to go alone. The only exception to this is home visits, which should always be done together.

How will I know when my patient is admitted or has an appointment?

All students will have access to EPIC, our patient management system, which will allow them to see admissions and appointments.

Essential Principles of Medicine (EPOM) - Part A and B

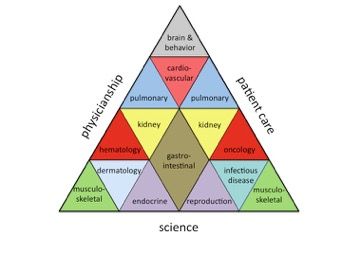

In the first curriculum segment (fall of year one), Essential Principles of Medicine students learn the core concepts of the three fundamental themes required for the practice of medicine: science, patient care and physicianship.

- Science domains acquaint students with basic science principles.

- Patient care concepts impart clinical skills.

- Physicianship education focuses on professionalism, ethics and humanism.

Essential Principles of Medicine fuses scientific and clinical learning, and is organized into several units:

- Pharmacology

- Genetics

- Cells, Tissues & Control Systems

- Metabolism & Nutrition

- Injury, Infection, Immunity & Repair

- Neoplasia

- Anatomy

- Patient Care & Physicianship

Course Directors

Michele Fuortes, Ph.D.

mfuortes@med.cornell.edu

Kathleen Bubb, M.D.

kcb4002@med.cornell.edu

Health, Illness & Disease (HID)

In the second curriculum segment (winter/spring of year one, fall of year two), Health, Illness & Disease bridges Essential Principle of Medicine and clinical clerkships. Students examine how various parts of the human body normally function, how they malfunction, how these malfunctions can be diagnosed and treated, and how these treatments affect society and the practice of medicine. The segment is organized by organ or organ system, with consideration for the interactions among systems. The three themes of science, patient care and physicianship introduced in Essential Principles of Medicine continue to guide the curriculum.

Health, Illness & Disease incorporates both novel and traditional educational methods, including:

- problem-based learning

- case-based learning

- "flipped classrooms"

- longitudinal patient experiences

- clinical skills workshops

- office preceptorship

- interactive sessions and small-group discussions

Health, Illness & Disease is organized into several units:

- Cardiology

- Pulmonary

- Gastro-Intestinal

- Renal

- Hematology Oncology

- Endocrine

- Reproduction

- Brain & Behavior

- Dermatology

- Rheumatology Musculoskeletal Medicine

- Infectious Disease

- Patient Care & Physicianship (Longitudinal)

Course Directors

HID 1 - Part A and B

Lawrence Palmer, Ph.D.

lgpalm@med.cornell.edu

Joshua Davis, M.D.

jad9165@med.cornell.edu

HID 2 - Part A and B

Teresa Milner, Ph.D.

tmilner@med.cornell.edu

Kristen Marks, M.D.

markskr@med.cornell.edu

Clerkships

Areas of Concentration (AoC)

For general information about the Areas of Concentration Program, please refer to Areas of Concentration page.

Translational Science

The goal of the Translational Science Course is to identify new advances in basic science that have current or potential translational relevance for clinical medicine.

At the end of this course, students should be able to:

| Learning Objectives | WCM Core Competencies | Assessment Method(s) |

| Summarize how advances in foundational sciences translate into new treatments, diagnostic tests, and new clinical approaches to human disease. | K-1, K-2, K-3, K-4, S-1 | Quiz |

| Explain how patient-oriented research can drive advances in bench science and basic science. | K-1, K-2, K-3, K-4, S-1 | Quiz |

| Determine how basic scientists and clinical investigators formulate a testable hypothesis relevant to the basis of disease. | S-1 | Quiz |

Course content information is provided by Course Director Henry W. Murray, M.D. (hwmurray@med.cornell.edu).

Additional information regarding absences, requests for absences, self-assessment quizzes, module evaluations, grading, or any other course-related issues is provided by Assistant Course Director Marshall Glesby, M.D. (mag2005@med.cornell.edu).

Advanced Clinical Ethics

Respect for autonomy is a prominent guiding principle in Western medicine and in medical ethics. Autonomous patients are often in the best position to determine what is beneficial for them, and therefore respect for autonomy generally promotes a patient’s well-being. In order to respect a patient’s autonomy, physicians are thus generally required to defer to patients' own decisions about how to manage their medical care.

However, respecting a patient’s autonomy is frequently easier said than done. The purpose of the Advanced Clinical Ethics Course is to explore some of the ways in which physicians’ duty to respect patients’ autonomy can become ethically challenging. First, respect for patients’ autonomy involves more than simply deferring to their wishes, and thus it imposes positive duties on physicians to both take steps necessary to promote autonomous decision-making and to eliminate obstacles to autonomy. Second, most patients lack the relevant decision-making capacity to make certain complex decisions regarding their healthcare, and thus someone else must be charged with making decisions on their behalf. On what basis should the surrogate make such decisions? And what are the obligations of physicians when they believe that surrogates are not making decisions in the best interest of the patient? Third, patients’ autonomous choices can at times conflict with physicians’ own autonomy. How should these conflicts be solved? Does the autonomy of patients always trump that of physicians?

Given that clinical practice is varied and complex, we identify and critically evaluate these questions and challenges by focusing on various areas of clinical practice, from end-of-life decisions, to organ donation, to reproductive choices, to pediatrics.

At the end of this course, students should be able to:

| Learning Objectives | WCM Core Competencies | Assessment Method(s) |

| Identify and analyze ethical challenges in clinical care, including strategies to prevent and manage ethical problems. | P-2, PBLI-3 | Faculty/Resident Rating, Paper/Essay |

| Describe the principles underlying the care of patients with pain and suffering at the end of life. | K-4, ICS-1, P-2, P-3 | Faculty/Resident Rating, Paper/Essay |

| Demonstrate the ability to navigate difficult conversations with patients, surrogates and colleagues while respecting cultural diversity and patient values. | ICS-1, ICS-2, P-3 | Faculty/Resident Rating, Paper/Essay |

| Demonstrate an ability to recognize and address clinician moral distress. | ICS-2, P-1, P-2 | Faculty/Resident Rating, Paper/Essay |

| Recognize the contributions of all team members in ethical decision making. | ICS-2, P-2 | Faculty/Resident Rating, Paper/Essay |

Any questions regarding the Advanced Clinical Ethics Course should be directed to Course Director Barrie Huberman, M.D. (bjh4001@med.cornell.edu).

Electives

Electives Catalog

The public catalog for Weill Cornell Medicine (MD program) is available in OASIS, here: https://cornell.oasisscheduling.com/public/courses/.

Clinical “away” electives provide exposure to new educational experiences and chances to explore residency opportunities. Weill Cornell Medicine uses the Visiting Student Application Service® (VSAS®) to process applications for fourth-year away electives at U.S. medical institutions.

Elective Codes

| WCM Electives | Electives Course Catalog |

| Away Electives | xxxx-8999 (Example: Medicine Away is MEDC-8999) |

| Independent Electives | xxxx-8998 (Example: Medicine Independent is MEDC-8998) |

| Global Health Electives | MEDC-89xx - Please see Office of Global Health Education (OGHE) for more information on available sites and specialties. |

Away Electives (U.S. & Canada)

Weill Cornell Medicine students wishing to take away electives must work in consultation with their advisor. Once a decision is reached about where to apply, students must access the visiting student section of that institution. Students are responsible for following the application guidelines of the away institution, and for submitting all paperwork required by both the away site and WCM. Medical schools use two general methods for accepting applications from visiting students.

VSAS Schools

Over 100 institutions (including Weill Cornell Medicine) utilize the VSAS Program to accept applications from visiting medical students. Rising fourth year students will receive further instructions from the Office of the Registrar.

Non-VSAS Schools

Many medical schools have their own application processes, which may vary widely in terms of length and requirements. Students should contact an institution to clarify their requirements before submitting an application.

Global Health Electives

Students interested in global health electives should visit the Office of Global Health Education. Questions regarding the elective and the application process can be addressed to globalhealthelectives@med.cornell.edu. Global health electives must be six-eight weeks in length, and require a project proposal, which is submitted for the approval of the International Committee. Additional information regarding opportunities and application processes is available from the Office of Global Health Education.

Independent Electives

Independent Electives are “customized” on-campus courses proposed by students that require sponsorship by Weill Cornell Medicine MD faculty. Some examples of independent electives may include:

- independent research with the approval of a sponsor.

- working with a sponsor on an elective topic that is not represented in the existing Electives Course Catalog.

Evaluation

WCMC faculty sponsors will submit evaluations of student performance in all electives completed at WCMC-affiliated hospitals. Students participating in electives at other institutions are responsible for providing the person at the other institution who will be evaluating their performance with an evaluation form. Credit for participation in away electives cannot be awarded unless a formal evaluation of completed work is received by the Office of the Registrar. Before leaving to participate in an off-campus elective, students should obtain an evaluation form. This form should be presented to the supervisor of the elective at the conclusion of a student’s participation, with the request that it be filled out promptly with exact dates and returned to the address printed on the form.

Summer Research Elective Credit

All WCMC students, starting with the class of 2018, have the opportunity to receive 4 weeks of Elective Credit for summer research conducted between the 1st and 2nd years of medical school.

You may apply for 4 weeks of Elective Credit provided:

- You complete 8 weeks of continuous research.

- Research is hypothesis-driven and is previously approved by the Director of Medical Student Research.

- You subsequently submit a "Documentation of Research and Final Approval Form" for approval by the Director of Medical Student Research.

More information and the application forms per class year can be found on the Office of Medical Student Research page here.

Health Policy

As future physicians, medical students witness first-hand how policy and other structural factors directly affect their patients' lives. This required course, which occurs after the majority of students’ clinical rotations, uses the framework of structural competency to explore the interconnection of health policy and health outcomes and discusses the role of physicians and other providers both in and outside the health care system. Through both lectures by local, regional, and national experts and practical exercises, students gain the language to describe situations and phenomena they have already experienced in their clinical years, such as structural vulnerability, structural violence, and moral injury. Sessions with experienced community research leaders emphasize the unique role medical students have in society, focusing on their opportunity and privilege to speak directly with patients whose lives depend on policy decisions.

Specific topics covered beyond introduction to key features of current health policy and health care financing structures, include exploration of notions of race and health correlates of racism, Medicaid policy, housing policy, food insecurity, immigration policy, science communication and misinformation, and others. Common threads throughout all content are a focus on health equity and structural racism. In conjunction with these expert lecturers, students additionally reflect on prior patients from their clinical clerkships, and discuss ways in which specific policy, resource allocation or structural factors affected health and wellbeing. With dedicated time to learn more specifically from experts in the fields of housing, the criminal justice system, immigration and beyond, the course aims to help students develop a fuller understanding of their patients’ lives, increase empathy, and decrease stigma within our healthcare system.

A key component of the structural competency framework is envisioning change. In their final assignment, students write about possible interventions addressing inadequate resources or ineffective policy. Many lecturers are real life examples of physicians actively engaged in areas of health equity research, advocacy, and quality improvement with aims to address health inequities and provide inspiration for our students, both in their assignments, with hopes of giving them options for their future careers.

| Course-Level Objective | Program-Level Learning Objective | Assessment Method(s) |

| Define structural competency and structural violence and their relation to health policy. | HCS-1 | Student case write-up, faculty graded |

| Describe the historical evolution of health care delivery and finance in the US, including key elements of the system as related to organization, financing, costs, coverage, access, and quality of care, including the new organizational modalities designed to contain costs (e.g. ACOs, P4P). | HCS-1 | Student case write-up, faculty graded |

| Identify key factors that drive health policy with an awareness of barriers to health equity such as structural racism. | HCS-1 | Student case write-up, faculty graded |

| Define quality assessment and patient safety as tools to promote health equity. | HCS-2 | Student case write-up, faculty graded |

| Generate strategies to apply methods of advocacy, community based research or quality improvement in order to mobilize correction of societal inequities that drive poor health outcomes.d | PBLI-4 | Student case write-up, faculty graded |

Co-course directors:

Amanda Ramsdell: akr7003@med.cornell.edu

Nathaniel Hupert: nah2005@med.cornell.edu